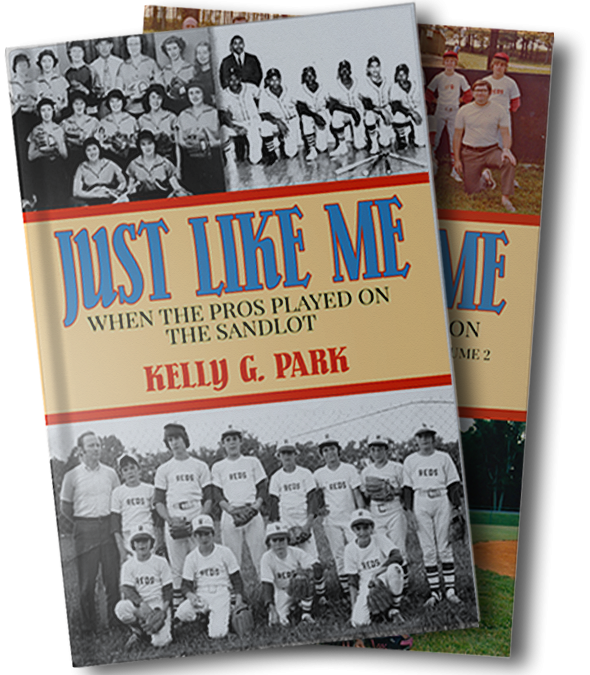

Kelly G. Park. Just Like Me: When the Pros Played on the Sandlot. Volume 1

Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunbury Press, 2020. 223 pp. Paperback, $16.95.

Kevin A. Johnson and Jennifer J. Asenas

Kelly G. Park was interested in the stories professional baseball players told about their youth baseball and softball experiences. But finding that such a collection did not exist, Park set out to do the work himself and interviewed members of the Hall of Fame, Major League Baseball, the Negro Leagues, and the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. These interviewed players include Boog Powell, Phil Roof, Hawk Taylor, Jim Hickman, Bill Greason, Lois Youngen, Katie Hortsman, Jim Kaat, Lou Pinella, Jim Zapp, Lou Whitaker, Steve Blass, Whitey Herzog, Doug Flynn, Fergie Jenkins, Willie Blair, Willie Horton, and Charlie Loyd. Park asked them questions a player or fan would want to know: Why did you pick baseball? Were you cocky or confident? What lessons did baseball teach you?

The topically organized stories shared will give the reader a glimpse into how the game used to be played. Park notes in his introduction that he began to “realize the historical aspect” of his interviews because “these players are telling me their experiences growing up that will never be experienced by kids again” (3). The stories in Just Like Me recount a time when baseball was simple.

Youth baseball used to be played with a lot less oversight. For example, Herzog recalls that during the summertime they “played baseball every day from 8:00 in the morning till our mothers came up to the schoolyard and said it’s time to go home and eat” (41). Similarly, Flynn recalls the freedom from parents on the sandlot and his father’s “distinctive whistle” that he used to call his son home (120).

The game was also, generally, played with fewer resources. For most of the players a “brand new, white baseball” was a luxury (Blass 131). Boog Powell said that they go to spring training and “come home with five or six balls and those balls were going to last us all year,” so they “taped them up” and used “bats that were nailed and taped and everything else”; they even made their own field (123). Some recall that equipment was provided by the team they played for (Whitaker 131) and that everyone on the team “used the same” bat (Roof 124). Whitaker had an uncle who was ten years older than him, and he would “always steal [his] uncle’s glove” (130). Yet they always found a way to keep the game going.

The game was also, generally, played with fewer resources. For most of the players a “brand new, white baseball” was a luxury (Blass 131). Boog Powell said that they go to spring training and “come home with five or six balls and those balls were going to last us all year,” so they “taped them up” and used “bats that were nailed and taped and everything else”; they even made their own field (123). Some recall that equipment was provided by the team they played for (Whitaker 131) and that everyone on the team “used the same” bat (Roof 124). Whitaker had an uncle who was ten years older than him, and he would “always steal [his] uncle’s glove” (130). Yet they always found a way to keep the game going.

As the parents of two boys who play baseball, we can attest that baseball, for the most part, is no longer played in this way. Phone apps are required to keep track of games, practices, and which uniform to wear. Players lug around bags filled with various, sundry equipment. Player statistics are posted on websites after tournaments.

But there are still parts of the game that remain unchanged. Kids still try to mimic their heroes. Roof recalls trying to suck “up as much knowledge as [he] could on TV back in the 1950s” (49). Bill Greason said he developed his “style after Vic Raschi” (53). And Kaat learned how to field his position as a pitcher by listening to the radio: “And here is Bobby Shantz, when he delivers the pitch, he lands on the balls of his feet, . . . he’s the best fielding pitcher in the game” (104). Kids still learn that no matter how good you are, there is always someone better. They learn “how to compete” and “how to fail” (120). But they still can find joy in the game and play with “reckless abandon” because they don’t know any better (69).

What’s interesting about this collection of stories is that while there is much that the players share in common, they are not monolithic. Some players were fans of the game; others were not interested in watching it—only playing. Some collected baseball cards; many did not. Some had parents who were athletes, and others came from families with little to no knowledge about baseball.

If you played baseball or softball or just love watching the games, you will enjoy reading Kelly G. Park’s book, Just Like Me. The interviewee’s responses will make you laugh, like when Hickman remembers the first time he tried chewing tobacco and got sick (100–101). You’ll shake your head when you read Youngen’s heartbreak when she was kicked off her team because they didn’t want to play with a girl (37). You’ll be disheartened to read about the indignity Greason suffered when he attended a baseball game wearing his Marine Corps uniform but was asked to leave because he is African American (201). And you’ll be delighted to read the story about Alvin Dark losing his job for wanting to start Ozzie Smith at shortstop on opening day and then years later being Ozzie Smith’s guest at Cooperstown when Smith was elected to the Hall of Fame (197).

These are but a few of the stories Park gleaned from his interviewees. He has done a wonderful service to the history of baseball by collecting and sharing these interviews. We are deeply appreciative that he included the narratives of African Americans and women so that a wider swath of the public who play the game can truly read this book and think, They were just like me.

© 2022 by the University of Nebraska Press

Recent Comments